The Storm provides.

In 2013, I wrote the first draft of The Pixar Theory, an essay that makes the case for how and why every Pixar movie takes place within a shared universe.

Just this past year, I published a book that finalized this draft into a more convincing and fleshed out read that you can check out here, but you can get a decent idea of what we’re talking about by reading the original article. Just keep in mind that much of what I wrote in that first blog post has been changed and improved on over the years.

Also this year, I posted how Inside Out (Pixar’s other 2015 movie) fits into the Pixar Theory, which you can check out here for even more context.

Yeah, I know it’s a lot of reading. As we talk about The Good Dinosaur below, I’ll do my best to add refreshers from past articles, so you don’t have to keep clicking around.

Needless to say, this post contains a lot of spoilers for The Good Dinosaur, so if you haven’t watched it yet and don’t want it spoiled for you, then check back later after you’ve had a chance to see the movie. You’ve been warned.

That said, it’s time to address a question I’ve been getting for over two years now…

THE BIG QUESTION

Does The Good Dinosaur take place in the same universe as ever other Pixar movie? Including Toy Story, Finding Nemo, and even Cars?

We’re going to address that question and then some. But first, let’s talk about something possibly more important. Let’s talk about what The Good Dinosaur contributes to the shared Pixar universe, beyond how it potentially “fits in.”

In other words, we’re going to talk about how The Good Dinosaur makes the Pixar Universe Theory better.

For one thing, it actually answers some major questions I’ve been asking since day one of putting this theory together. And I know plenty of people have wondered this too:

WHERE DOES “MAGIC” COME FROM?

If you’re at all familiar with this theory, then you’re plenty aware of how magic plays a mysterious role in the shared universe of Pixar. But one thing I’ve never fully understood is where it’s supposed to come from in a world where animals can cook and toys can talk.

I’ve claimed in the past that the wisps of Brave are where this magic originated, or at least point to magic tying in with nature somehow. I’ve also posited that wood is a source of magic, which is certainly evident given how doors have dimension-defying capabilities in multiple Pixar movies, including Monsters Inc, and Brave.

Humans can use magic from what we’ve seen, or at least some type of it. In my book, I argue that the supers from The Incredibles received their powers through government experiments in order to be spies (at first), which would explain why they seem to have military experience and backgrounds in espionage.

But it’s unclear how technology could make a person fly. It’s unclear how Boo from Monsters Inc., could harness the magic of a door and travel through time. It’s unclear how humans of the distant future could find a magic tree with fruit that could transform them into animalistic monsters (a tidbit from the Monsters Inc., DVD).

But with The Good Dinosaur, we finally have a suitable theory for where this magic comes from, as well as a proper starting point for the Pixar Universe.

THE SET UP

The film opens 65 millions years in the past, when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. The opening scene clearly shows us a world like the real one you and I live in, where animals eat from the ground and have primitive senses.

In reality, it’s believed by many that an extinction-level event is what caused the disappearance of the dinosaurs as we know them today. A predominant theory is that an asteroid wiped all of these creatures out, long before mammals like humans ever came to be.

Pixar accepts this premise and turns it on its head by proposing a world where there is no extinction of the dinosaurs because the asteroid misses Earth entirely. Millions of years later, dinosaurs are still the dominant species on a very different-looking planet, while humans are just now arriving on the scene.

One thing I love about The Good Dinosaur, by the way, is how the film doesn’t rely on any exposition to illustrate what’s taken place since the asteroid missed Earth. We just see an apatosaurus family tending to their farm. Right off the bat, we learn that dinosaurs have become the most intelligent creatures in this world, able to provide shelter, fences, and resources for themselves and other creatures.

They’re smart. They use their appendages in unique ways to ensure their survival. It’s a simple reimagining, but it’s effective. And it parallels nicely with what we’ve come to expect from future animals in the Pixar Universe, notably Remy from Ratatouille, an animal who manages to become a better chef than any other human (in Paris, at least).

So right away, The Good Dinosaur hammers the point that when left to their own devices, animals can become just as intelligent as humans, as we also see in A Bug’s Life with Flik’s inventions and ingenuity ensuring the survival of his entire community.

In the same way, the apatosaurus family of The Good Dinosaur relies on the harvesting of food to get them through a harsh winter. Arlo, the main character, is the youngest of three siblings to the apatosaurus parents who run the farm. To “earn his mark,” Arlo is given the responsibility of catching a feral critter who keeps stealing their food.

We eventually learn that this critter is what we know as a human. He’s a small, wolf-like boy who doesn’t appear to have his own language beyond grunts, and Arlo adopts him has his pet after the two get washed away by the river, far from home.

From there, the movie shows us their long journey home, and a lot happens over the course of these few weeks. We learn quickly that this part of the world suffers from frequent storms, some of them looking like typhoons. Later, it’s evident that very few dinosaurs are around, despite the fact that they’re the most intelligent species around.

We see a few dinosaurs along the way, but only in small groups, rather than herds. Towns and settlements are apparently scarce, but still alluded to. And every dino is obsessed with survival.

Forrest, the Styracosaurs, chooses to live in the wilderness under the protection of the creatures he carries around with him. This is played off as a joke, mostly, but it shows just how harsh life is in this world for reasons that are left to the imagination.

It’s also telling that Forrest is just as fearful as Arlo, and with good reason. There’s not much food around, and though these dinosaurs are smart, some are being born with an innate (possibly learned) sense of fear.

We certainly get a feel for how scarce resources are by the time we meet the hybrid Nyctosaurus gang, led by Thunderclap. I say hybrid because like the other dinosaurs in this film, they have many traits that have evolved from the fossils we have on these creatures. In fact, every creature in Thunderclap’s gang is a different species.

These flying creatures are a “search and rescue” team who scavenge the helpless creatures traumatized by the frequent storms. “The ‘Storm’ provides” is not just a weird catchphrase for these beasts—it’s their religion. They worship the storm for giving them much-needed food.

Isn’t it strange that Arlo got sick from eating plants that weren’t fruits like berries and corn? Millions of years earlier, we saw dinosaurs eating grass just fine, so what changed?

Before we get to that, it’s important to point out how the T-Rex family manages to survive. They have to raise and take care of a bison herd by themselves in order to have enough food, often fighting off vicious raptors desperate for their food. And the T-Rexes are constantly on the move, which probably has something to do with how the environment is too volatile for them to settle down anywhere, as well as the fact that they have to find enough food to feed their food.

WHY?

If dinosaurs have been evolving for millions of years, then why are they having such a hard time, now? In the opening scene, there are many dinosaurs all eating together without a care in the world, so something big had to happen between those good times and the bleak world we’re introduced to countless years later.

Well, I think it’s pretty simple. These dinosaurs are living in a “post-apocalypse” of their own civilization. At one point, they probably had plentiful resources to sustain a massive population, much like you’d expect. But what we see is a shifted environment. The lush jungles filled with edible plants that we know existed millions of years ago have vanished by the time we meet Arlo, just as they would have if the asteroid had hit Earth.

Simply put, the world slowly became less optimal for the dinosaurs to roam, which the movie goes out of its way to illustrate. Arlo’s family is on the brink of running out of food because rival creatures like the mammals (AKA humans) are stealing their food and thriving in this new environment. These storms are a product of this change, as the world gradually corrects the imbalance of reptiles and mammals caused by the lack of an extinction-level event.

And many years later, the same “correction” will happen between man and another new species: machine.

In other words, Pixar loves cycles. And the Pixar Universe is as cyclical as they come. It’s actually pretty amazing how a simple movie like The Good Dinosaur offers such a close parallel to stories they’ve already told, Pixar Theory or no.

WHAT ABOUT THE OTHER PIXAR MOVIES?

If The Good Dinosaur exists in the same timeline as movies like The Incredibles and Finding Nemo, then where’s the evidence of those movies being a result of this alternate universe where dinosaurs ruled the Earth much longer than planned?

What about fossils? Certainly, the Pixar movies would exist in a world where the fossil record is drastically different. What about these strange creatures in The Good Dinosaur that don’t look like any animals we’re aware of, like the dreaded cluckers?

Well, that’s where Up comes in.

Early on in Up, we see that the famous explorer Charles Muntz has found a place in South America filled with plants and animals “undiscovered by science.” That place is Paradise Falls (or, “The Lost World” as the narrator puts it).

And what is the prize creature that Muntz discovers? It’s no dinosaur. It’s a bird (Kevin). And this is a bird that bears resemblance to the bizarre makeup of the “prehistoric” birds and raptor-hybrids we see in The Good Dinosaur, who have originated from this alternate universe where evolution was never halted.

And that’s not where the weirdness ends. Cut from Up is the explanation for why Charles Muntz is still spry and healthy, despite being much older than 80-year-old Carl Fredericksen. According to Pixar, Muntz found Kevin’s eggs, which somehow have the ability to slow down the aging process (my book covers this in more detail, but that’s the gist).

So Kevin’s existence, as well as this rare, superhuman ability, finally has an explanation. Somehow, the longer evolution of these strange creatures brought about magic — or at least something that resembles magic — that can eventually be harnessed by humans in various ways. After all, what is it really that makes those dogs in Up talk? And is it any surprise that Muntz comes across Kevin’s existence in the 1930s, not long before the sudden rise of supers with strange abilities?

Remember: The Incredibles takes place in an alternate version of the 1950s and 60s. Mr. Incredible was very young or even born around the same time Charles Muntz was uncovering what could be “magic” properties. This could even serve as an explanation for why academia suddenly turned on Muntz, shaming him for what we know weren’t fraudulent discoveries. Perhaps this was a ploy to keep his research hidden from the world, explaining why only Americans are shown to have powers in The Incredibles.

Sometimes I get goosebumps when these things fit together a little too nicely.

OK, what about the strange animals mentioned earlier? Well, when we explore the dirigible in Up, Muntz shows off his collection of these strange creatures that are so rare, Muntz doesn’t expect Carl to know what they are.

They range from giant turtles and other aquatic life to hybrid mammal/dinosaurs that are reminiscent of Forrest from The Good Dinosaur. And we can now deduce that in the Pixar Universe, many of these creatures existed closer together in time, explaining why they’re displayed as a group.

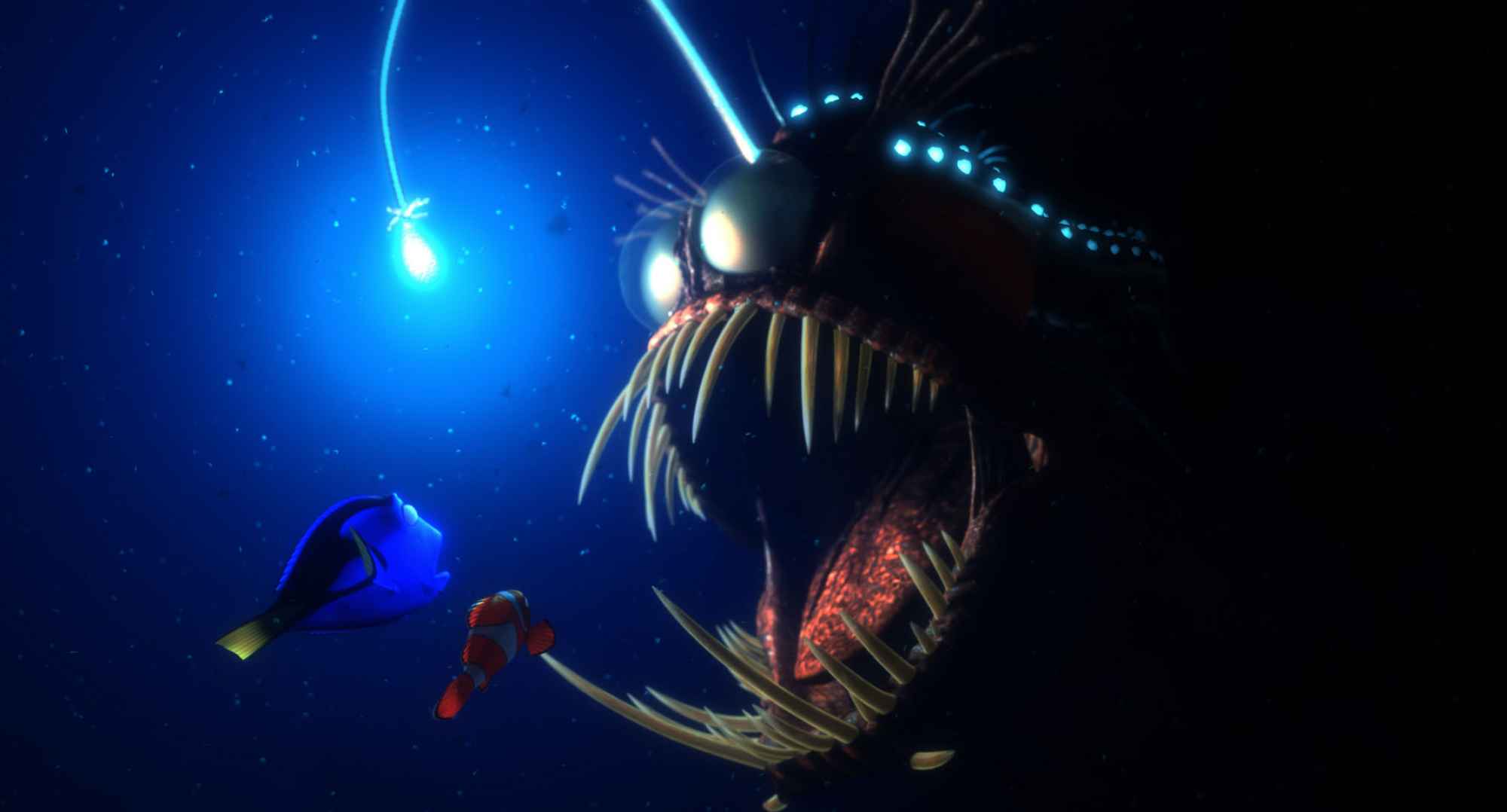

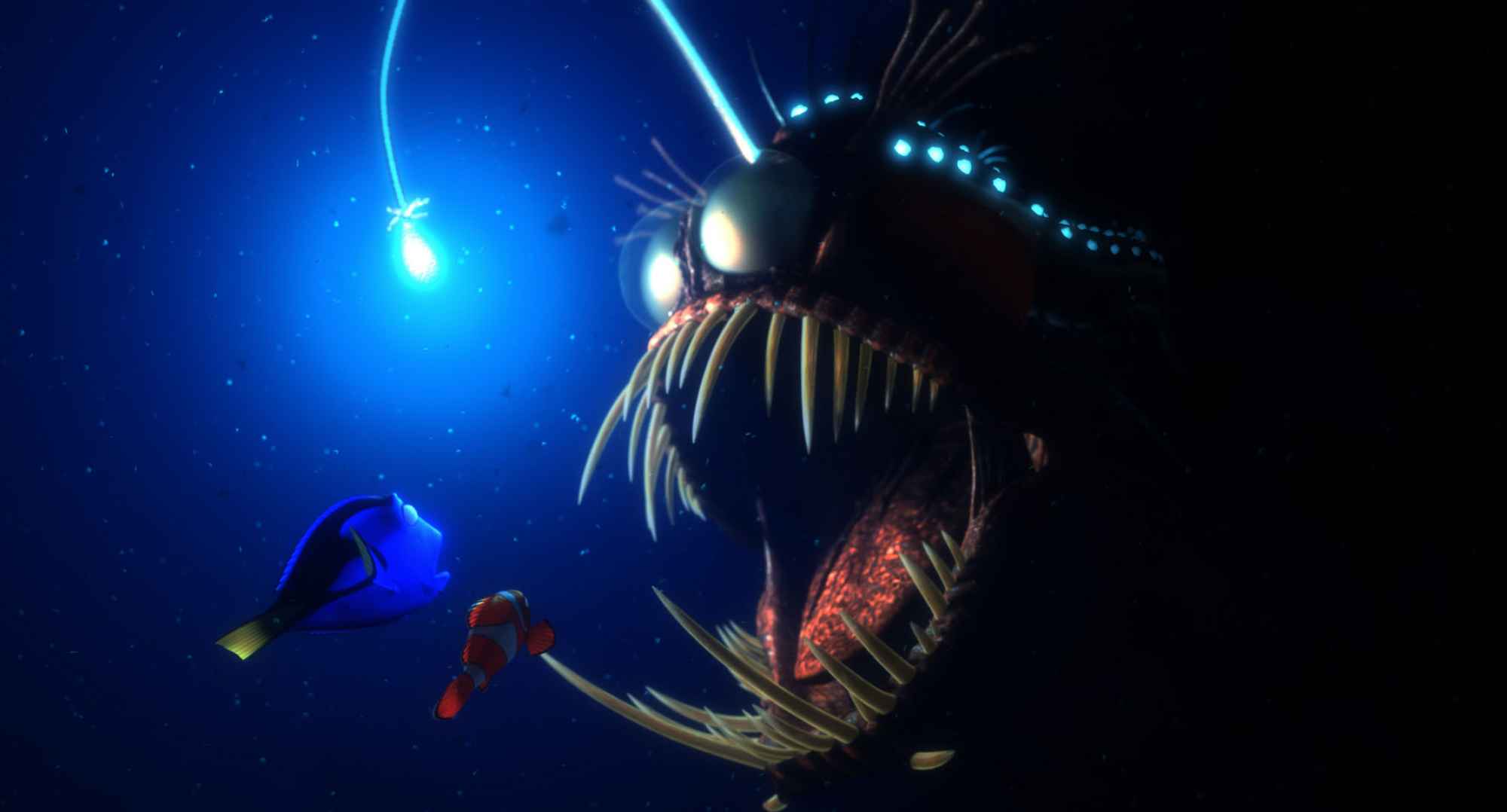

Side note: One of the reasons I’ve waited to add all of this to the Pixar Theory is because I’m still researching how these creatures connect to other movies, including the angler fish that looks just like the one we see in Finding Nemo.

So the exotic creatures from The Good Dinosaur apparently exist across multiple Pixar movies, and the absence of an extinction-level event seemingly provides an explanation for why animals have become so intelligent by the time we get to movies like Ratatouille. And the movie even provides some hints as to why magic exists in the Pixar Universe, and we now know why said universe is alternate to our own.

Is that it?

Ha, no.

FOSSILS AND FUELS.

Oil. It’s something that Axelrod from Cars 2 addresses as the very thing we get from fossils, which he specifically defines as “dead dinosaurs.” But for whatever reason, the world runs out of oil in the Pixar Universe much sooner than we would by today’s standards.

Drilling the way we are today, there’s probably 50-100 years of oil left, which obviously excludes methods that dig much deeper. So really, we’re just running low on cheap oil.

In Cars 2, the sentient cars are running out of oil, entirely. And this makes sense for two major reasons:

- Mankind has a 200 billion population by 2105 (according to WALL-E)

- There’s less oil on Earth because (whoops!) dinosaurs died out more gradually.

Fossil fuels bring life to us from dead organisms, and we get a lot of it from extinction-events that compact them for easier extraction through drilling (for the record, my knowledge on this topic goes about as far as Armageddon).

Without the asteroid, fossil fuels are a bust.

In The Incredibles, technology has progressed more rapidly by the 1950s, likely because scientists are seeking solutions to this energy crisis. Syndrome finds a way to harness zero-point energy, and “human” energy will be extracted by toys and eventually monsters indefinitely. The absence of other energy options like fossil fuels might provide an explanation for why human energy is so important in the Pixar Universe.

Yet in WALL-E, mankind lives in a loop for hundreds of years aboard starliners like the Axiom. They harness solar energy with advanced technology that allows them to avoid the laws of entropy (and you can argue that the machines are also kept alive by the humans themselves).

All this points to a world that figured out (much faster) that it needs an alternative to fossil fuels, which is why humanity is still around hundreds of years after the cars die out.

THE LEGACY OF DINOCO.

So in the Pixar Universe, dinosaurs eventually die out because the world changes without them. But they’re remembered, nonetheless, mostly because humans have passed down their memories of the once predominant species.

By the time we get to “modern Pixar,” there are companies like Dinoco that use these forerunners as their logo. Toys like Rex and Trixie get played with, just as they would in our world. There are even statues in Inside Out that look like dinosaurs we see in the movie.

The major difference is that in The Good Dinosaur, there’s a specific “passing of the torch” moment between Arlo and Spot. The symbolism is actually tragic in a way, as we see Arlo giving Spot over to a human family willing to adopt him. Unlike Spot, these humans wear furs instead of leaves and alternate between walking on all fours and standing upright, even teaching Spot how to do it by guiding him. This moment crystalizes the rise of mankind in contrast to the dinosaurs, who are quite literally on their last legs.

After all, Arlo will return to his farm and eke out a pretty humble existence as a herbivore. His family will barely survive, as his mother tells him bluntly early in the movie. Meanwhile, humans are already hunting and living off of the newer resources tailor-made for mammals. Pixar could have easily left these implications out, but instead they shine a light on the important role mankind will take up as the world continues to change.

That said, I suspect there are more mysteries to solve here. We have millions of years of history between The Good Dinosaur and Brave, so you can expect brand new narratives to rise out of those films as the studio continues to deliver excellent movies more than worthy of our time.

WRAPPING UP.

That’s the long version of how The Good Dinosaur fits within the narrative of The Pixar Theory. But I hope you’ve also gotten some insight into why it’s so important to the theory, in a way that not even Inside Out was able to accomplish, though it also was quite enlightening.

With The Good Dinosaur, we have firm answers for some of the biggest questions many have come across when digging into this theory. It gives us a reason why everything in Pixar movies is so different and set apart from reality. It alludes to the mysteries of magic with a little help from Up, further providing connections I didn’t think we’d ever get.

And we even got Dreamcrusher.

I hope you enjoyed the movie itself as much as I did. My full review is also available in case you’re not already tired of reading, which you can check out here. You’ve probably noticed by now that I’m absolutely in love with The Good Dinosaur, and the review expands more on all of that.

As for the easter eggs, this movie has proven to be quite the challenge when it comes to finding the elusive Pizza Planet Truck and A113. Peter Sohn (director of the movie) confirmed they’re in there somewhere, albeit in clever ways similar to how Brave managed it. I haven’t caught them yet, but I’ve heard the truck shows up as either a rock formation or an optical illusion from the positioning of several rocks and debris. Be sure to share your findings.

Let me know your thoughts, ideas, and rebuttals in the comments, and I’ll do my best to clear anything up!

Ready for more?

The conspiring doesn’t end here. Check out my other Pixar Theory posts from infinity to beyond:

- The Pixar Theory – the full book available on paperback and ebook via Kindle, Barnes and Noble, iBooks, or just a PDF. This will cover the entire theory and every movie in the Pixar universe, updated from what you just read.

Thanks for reading this. To get updates on my theories, books, and giveaways, join my mailing list.

Or just say hey on Twitter: @JonNegroni

Like this:

Like Loading...